Actual Game

Betrayal at Krondor1-Click Install

|

In Raymond E. Feist's multi-volume "Riftwar Saga," two worlds are joined by a magical corridor: Kelewan, the alien world of the warlike Tsurani, and Midkemia, the world of the protagonists - a Middle Earth-like land of elves, dwarves and dragons. In creating Betrayal at Krondor, a fantastic early 90s RPG from Dynamix, a corridor exists between three worlds: the world of people-and-paper role-playing where the Friday night gaming group of Feist and his friends created the land of Midkemia, the literary saga of Midkemia's history in the Riftwar novels and, returning almost full circle, the world of computer role-playing where Design Team Leader John Cutter magically transforms the Midkemian mythos into a three-dimensional environment.

Readers of Feist's books will want to know that the game is set between A Darkness at Sethanon and Prince of the Blood. Everyone else will be relieved to know that there is a very good summary of prior book events in the manual, and that Dynamix has taken pains both there and in the game to describe things for newcomers. Briefly, ten years ago a major army of elves from the north was defeated and the charismatic leader who had unified them under his banner was slain. Now trouble is brewing again in the north -- a new leader has arisen, and is acting in ways that hint at hidden plans. The party of three characters you control, as agents of the Kingdom, must find out what is going on... and take appropriate action from there.

Midkemia is an ideal gaming environment. The world is large and peopled with fantasy races. Though most of the feudal lords pay homage to a central king, the government is practically balkanized enough to be subject to civil war breaking out at any given time. This makes for plenty of intrigue within the ranks of the protagonists' own kingdom. Then, there is the threat from without (whether the Midkemian Empire of Kesh or the Tsuranuanni Empire of Kelewan) and the mysteries of antiquity (the Valheru and the devastation of the Chaos Wars). All add to the "gameability" quotient of the universe.

The use of Feist's world of Midkemia makes for a very solid, consistent environment to play in. The cities in this game have histories, and the motives of their inhabitants are molded accordingly. In this game the moredhel (enemy elves) aren't mean and nasty "just because"; there are reasons for who they are, how they became that way and why they're upset at the Kingdom, and these are continually reflected in the script and conversations over the course of the game. Likewise one doesn't have cities sewn out of whole cloth as "the city of beauty", "the city of warriors" or "the city of wizards". Instead, one has LaMut, a queer place on the northwest frontier with a large contingent of Tsurani immigrants from the Riftwar; or Armengar, a city being slowly recolonized by the moredhel after its utter destruction in the recent war; or Silden, a port town for traffic with the exotic and decadent Keshian Empire. Simply because there's no one to put the time or genius into them, this level of depth in plot and environment is unheard-of in other RPGs. Here, the use of Feist's work gives the entire world a much stronger sense of solid reality, regardless of whether the player is familiar with the works. Even when there are relatively few things to do in a given place, the quality writing and the use of Feist's material gives it much more atmosphere than other games provide to their locations.

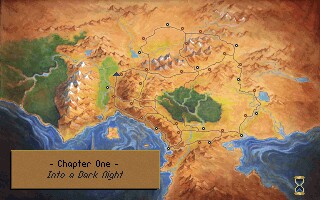

Like Elder Scrolls: Arena, Betrayal at Krondor uses a 3D interface that has the feel of a flight simulator brought to ground. You use the directional arrows and compass at the bottom of the screen and move the party of characters along a step at a time. Then, once the party is in the center of a road, the gamer can toggle an "auto-road" feature and place the cursor over a directional arrow. By holding down the mouse button, the party will simply blitz down the road, affording a movement bonus for being on the road that is visually communicated to the gamer rather than numerically presented. Indeed, if one so desires, it is possible to zoom high above the party in an overhead map view and zip down the road so fast that one has a sense of flying. The effect was amazing in 1993 and has since become a staple in adventure game presentation.

As players encounter on-screen enemies, they occasionally hide behind terrain features such as trees and come out to ambush the party or they scale larger as they come closer and smaller as they flee. When players encounter on-screen objects, they scale as the party closes or broadens range on them. One need only click the right mouse button to determine what an object is and the left mouse button (once the party is close enough) to examine the object. We also liked the shading - and brightening that constantly indicated the cycling of day and night. Much of the Dynamix visualization of Midkemia was considered stunning, but Cutter's team has established a solid corridor between the technological interpretation of the world and the literary interpretation of the world via a lavish use of text. The entire game is structured according to chapters in a book, a book which would feature events taking place between A Darkness at Sethanon and Prince of the Blood. As the player solves each portion of the game successfully, another chapter is introduced. The pages of text are presented in a beautiful, illustrated manuscript format and are occasionally enhanced by images of the characters and animated sequences (with the limited movement of some early Japanimation). It is very obvious to even the most casual fan that the writers must have studied Feist very thoroughly or collaborated effectively with him. The tone of the text is just right.

When the player's party encounters a non-player character who is not bent on immediately attacking the party, there is a digitized on-screen photograph of the character displayed on the screen. Much of the conversation is handled via the text pages indicated above, but the program also parses the subject matter of the NPC's conversation into clues for the player. Thus, when the NPC is finished with his/her canned speech, a screen appears with a set of on-screen buttons. Many or, conceivably, all of these buttons will list potential new topics for the NPC to discuss. All the gamer needs to do is point and click on one of these active topic buttons and the NPC goes on with the conversation. At the end of this new information, there may even be more topic buttons available. In this way, the player can extend or suspend the party's conversations with NPCs by either selecting new topics or not.

Combat is handled very elegantly in Betrayal at Krondor. The gamer's party of characters and any bad guys or monsters appear in the 3D image area at the top of the screen. Then, in a phased movement where the sequence is governed by the character's Speed rating, characters move and/or swing/spellcast in descending order. For tactical movement, the gamer moves the cursor until a green rectangle appears on the 3-Space ground where the character should finish his/her move. If the character is in range to attack, a yellow rectangle will appear around the feet of the enemy as the gamer moves the cursor toward the enemy. If the character can cast magic at the enemy, a blue rectangle will appear around the feet of the enemy. If the gamer wishes to strike, he/she need only make a mouse-click while the yellow or blue rectangle is in place, Damage, if any, is immediately assessed and the turn progresses to the next fastest character or enemy. Combat continues until one side is destroyed or successfully retreats (the combat AI is smart enough to retreat, often).

Note: After combat, it is wise to select the campfire icon and "Camp Until Healed." Characters can restore up to 80% of their strength in this way, even without benefit of healing spells. Feist does not elaborate very much on the magical system used in either Kelewan or Midkemia. So, Cutter's team was forced to fill out the references. In the first book of the series (either Magician in hardbound or Magician: Apprentice in softcover), Kulgan speaks of Pug understanding the logical structures of magic. Later, in softcover's Magician: Master, Pug is informed by his alien mentor that Midkemian practitioners only understand part of the structure of their magic. Once a gamer clicks on the amulet icon, a spellcasting menu appears. The spellcasting menu consists of several spell circles containing geometrical forms with arcane symbols in each area of the diagram. Assuming that the character can cast a certain spell, the gamer need only move the cursor over one of the arcane symbols and the name of the spell will appear, along with the range of damage said spell could cause and the potential cost in energy (Health points) should the character cast it.

With some spells, many of the small dots on the outside of the spell circle will be highlighted. In such a case, the information on damage and energy (Health) cost is dynamic and changes as the gamer moves the cursor along the outside of the spell circle. This is because the different dots on the outside of the circle represent the amount of Health which the spellcaster is willing to put into casting the spell. Once the spell is selected and the amount of energy to be placed into casting it is determined, the view returns to the combat screen. Then, the gamer need merely ascertain that the blue rectangle is placed around the enemy's feet and click the mouse button. The visual effects are often very striking with enemy's turned into stone and shattering into dust or burned to a crisp and frittering into ash.

Naturally, as characters advance, there are more and more geometrical diagrams to be discovered and, hence, more spells to be cast. In a real sense, the magic system for the computer game seems very much in tune with the spirit of the magic system at which Feist hinted in the books, but did not detail. The magic system will not satisfy gamers who wish to gather spell components or mix potions, but it should satisfy those who have read the Riftwar series of novels.

Betrayal at Krondor bridges the gulf between three fantasy environments and is superb for three basic reasons: Aesthetics, interface, format and game play; extraordinary innovations in combat and story development; and not making any of the stupid design mistakes of other recent computer RPGs then available. Dynamix parlayed a license to Feist's work, solid game design, and quality writing of its own into a game that has more substance underlying it than anything else on the market at the time. Equally important is that Dynamix managed not to cripple the enjoyment of the game with an excess of combat or linearity or boredom. The result worked then -- and still hold true today. Betrayal at Krondor is what a game derived from a licensed story should be.